Our seas are choking on 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris.2 Our reefs are suffocating from a lack of oxygen and changing chemical composition. Over 100 million marine animals and seabirds die every year from human pollution.2 And now, we know that microplastics have made their way up the food chain and are detectable in human blood samples.5 It’s more than just a dirty beach.

On the bright side, we now have a very clear picture about the state of the world’s waterways and the impacts humans have had on marine ecosystems since the Industrial Revolution and the advent of widespread plastic production. With over $40 billion7 in private market eco-investments last year, startups focused on ocean cleanup methods, marine ecosystem preservation, and plastic alternatives are receiving record venture funding. Given the overlap between marine ecosystems and our everyday lives, capital directed toward the cleanliness of our waters promises an immeasurable impact for generations to come.

Where is it Coming From?

Our waterways are being affected on several fronts, both seen and unseen. Not only is pollution due to conscious carelessness in littering and dumping, it’s also an unintended consequence of everyday human activities. The types of pollution can be grouped into three distinct categories – (1) chemical changes from external additives, (2) plastic debris from littering, and (3) noise from human activity. Each of these poses a unique threat to the world beneath the waves; a world more interconnected than most humans realize.

Chemicals

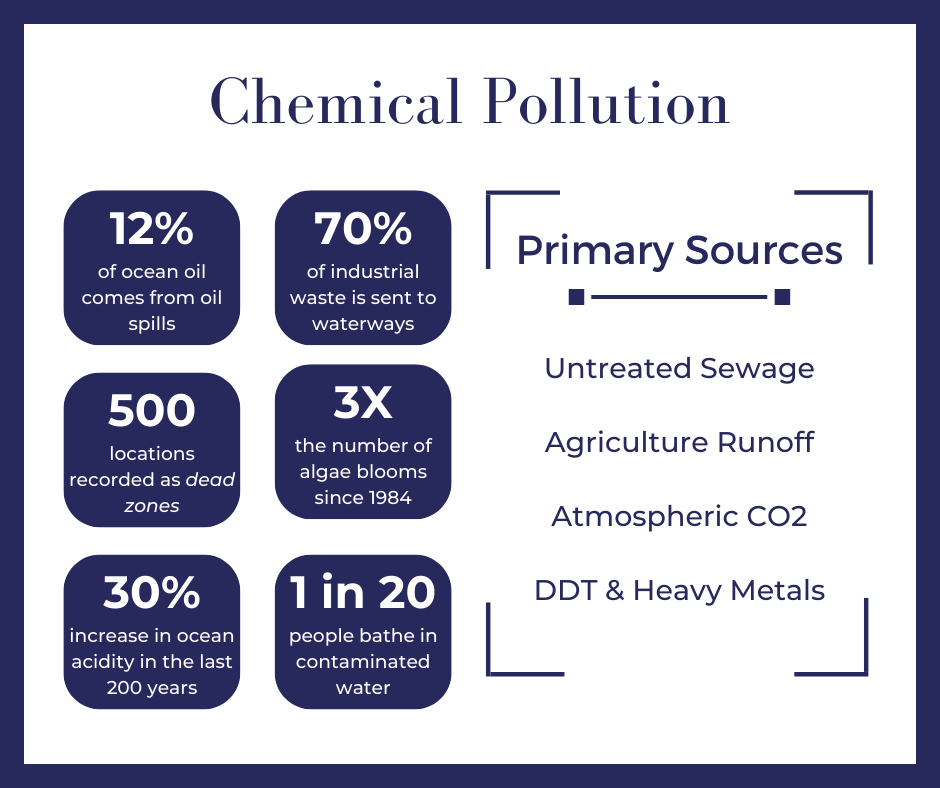

As levels of atmospheric CO2 increase from the continued use of fossil fuels and the practice of deforestation, the ocean acts as a sponge and absorbs excess carbon dioxide. The dissolved CO2 combines with water to form carbonic acid that in turn decreases the pH of the seawater. Since the industrial revolution, the acidity of surface ocean waters has increased by 30%2. Ocean acidification is particularly impactful for fragile coral reefs and the 25% of marine life that live in these unique habitats2.

In addition to acting as an atmospheric sponge, the ocean unintentionally functions as the world’s storm drain. Heavy metals, DDT, pesticides, and 80% of untreated sewage2 flow into waterways by way of natural runoff and human negligence. The consequence is eutrophication – a critical reduction in oxygen levels – and over 500 uninhabitable ‘dead zones’ across the globe.

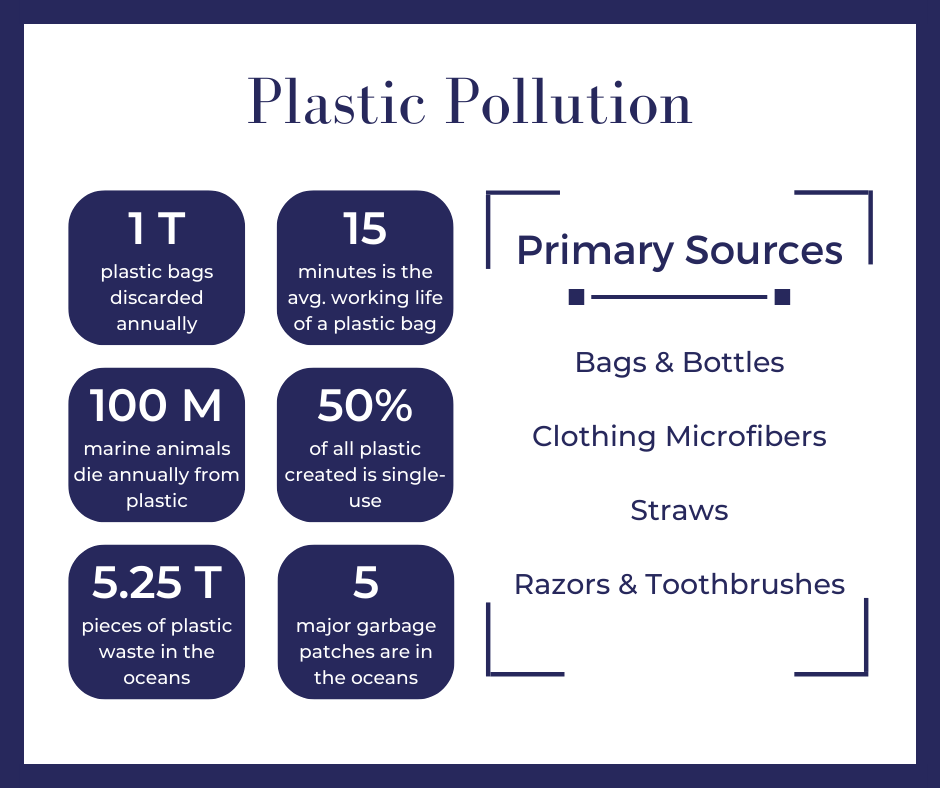

Plastics

Invented in 1907 and mass produced starting in the 1940’s, 100% of all plastic ever created is still in existence today3. Over its 500-year lifespan, plastic is gradually stripped down into microplastics and takes up residence on the sea floor, ocean surface, and our favorite beaches.

But where else does it go? In 2019, a dead sperm whale washed up in Scotland with more than 220 pounds of tangled netting, rope, and plastic inside its stomach6. And that wasn’t the first time. In 2018, a beached sperm whale in Spain contained more than 60 pounds of plastic trash, and in 2008 two whales died in California with ruptured rubbish-filled stomachs6. These examples, and many others, serve as a grim reminder that the man-made debris in the ocean has a material impact beyond the unsightly 1.8T piece Great Pacific Garbage Patch1.

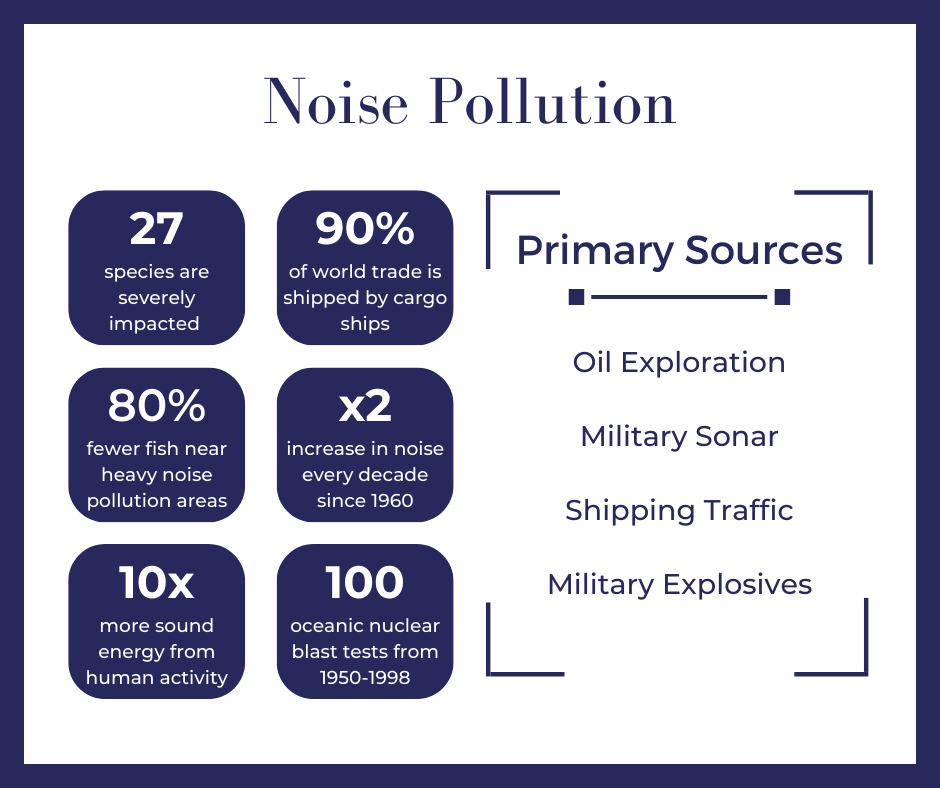

Noise

The ocean without anthropogenic intrusion is a silent world. For marine animals, this is vital. They use sound to navigate, communicate, find food, locate mates, and avoid predators. This biological system experiences intense interference from oil exploration, military sonar, and mass cargo shipping.

With noise levels doubling every decade for the past 60 years4, our activities have created an ever-present and rising aural fog in the ocean. Consequences of noise pollution are devastating to fish and marine mammal populations. The primary impact is migration – animals moving out of areas with cacophonous noise to depths or ecosystems not native to their species. This is demonstrable in the beaching of whales near Navy routes and the decline in catch rates near unregulated waters.

Futile Efforts

Over the past decade, a variety of notable efforts to clean up the ocean have been deployed all with one thing in common – they made little difference. Of all the plastic plaguing our seas, only 15% of it floats and 15% ends up on beaches. The other 70% sinks to the bottom2. While these endeavors are ineffective at solving the problem, they do succeed in disturbing microorganisms and releasing additional carbon emissions.

Once plastics and foreign chemicals have made their way to the ocean proper, they are pulverized and diluted. Ocean gyres gather these pea-sized fragments into what we call garbage islands, but these pollutants actually form something more similar to a soup within the sea.

Optimism for the Future

As many startups make valiant efforts to remove trash from the ocean, the simplest solution begins with preventing the annual dumping of 12 million metric tons1 into our waterways. We can achieve this first by reducing the amount of plastic produced and second by capturing the dumped trash and runoff at its main entry points, rivers.

Ten rivers (8 in Asia and 2 in Africa) contribute to 90% of global ocean debris2. Entrepreneurs are piloting, deploying, and scaling different filters that can be placed at the mouths of these rivers to capture pollutants before they ever reach the ocean.

To acquire a deeper understanding of how to stop the Aquacalypse we must examine historical ecological accounts. We can look at a time, in 1883, when the English biologist Thomas Huxley asserted that “all the great sea fisheries are inexhaustible”. We should take note of moments in the 1500’s when Europeans dropped baskets near shore-waters and hauled up masses of large cod. When whales seemed to be “infinite in number” and Spanish sailors saw turtles “in such vast numbers that they covered the sea”. Diving into what the ocean once was demonstrates the intense damage humans have caused and a potential picture of what (with a dedication, capital, and innovation) it could look like once again.